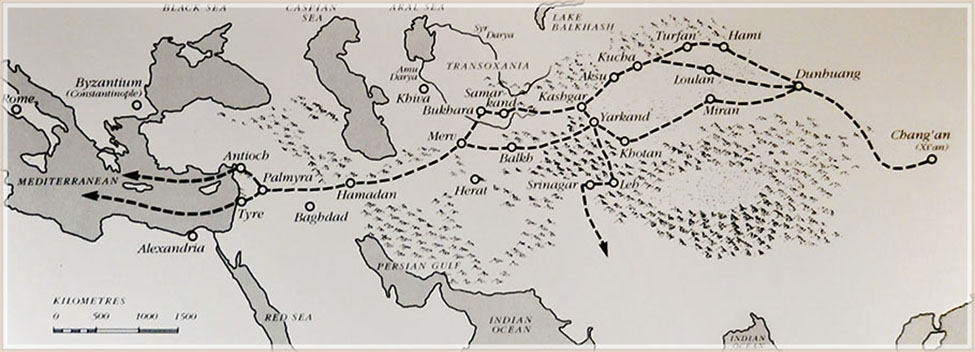

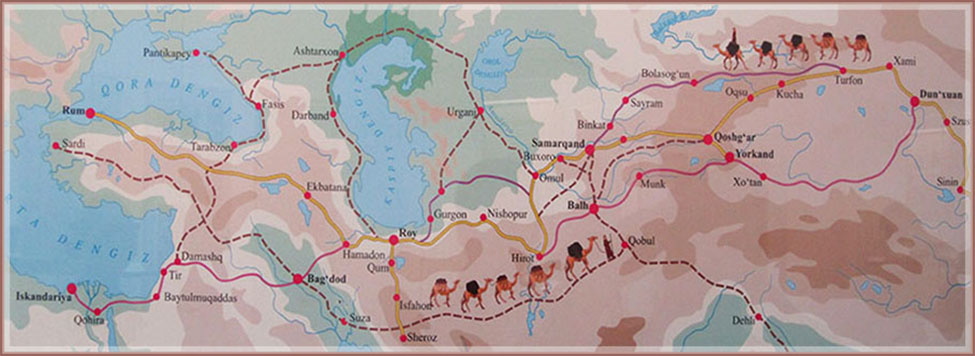

One of the most important developments in Central Asia was the arrival of the Silk Road, which connected China and Europe, providing a vital trade link between the East and West. Cultural exchanges were made through what was in fact, not just one, but a network of trade routes. Religion, technology, textiles, most notably silk, spread from China to the Western world. Central Asia, through which the Silk Road passed, benefited greatly as Chinese goods were brought into the region.

It is not a coincidence that the oldest needles, made of bone and ivory around 40,000 B.C.E., were found in Central Asia. Thus, it is generally acknowledged that sewing was first invented there. The first textile found in Central Asia is dated around 3,200 B.C.E., from the North Caucasus Majkop culture. This textile is made of wool and is so far the oldest archaeological find in that material. By 3,000 B.C.E., herders in Central Asia used sheep’s wool to make striped cloaks and skirts. They also made costumes out of hemp, a wild plant which grew all over Central Asia.

One of the earliest known knotted pile rugs, an almost complete example, is the Pazyryk carpet, found in a frozen Scythian tomb in Siberia. This rug, which is dated to the 4th to 5th century B.C.E., is now at the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia. Interestingly, it uses the same symmetrical knot that was historically favored by Turkic weavers in Anatolia up until the present day.

As trade routes between China and Europe developed, small cities were established along the Silk Road. These cities were usually located near oases where their inhabitants could supply themselves with enough water to survive. These oasis towns functioned as markets along the Silk Road. Merchants would stay in these towns and prepare for their long journeys. The Silk Road brought great wealth to Central Asia. Silk was introduced into this region from China. Ikat weaving skills, although it is uncertain where exactly they came from, were also brought into the region. Consequently, wealth, culture, religion, and technology were also transported along the Silk Road. Such cultural influences were greater in oasis cities than in nomadic societies, mainly because oasis cities had more contact with the merchants who traveled along the Silk Road.

Oasis dwellers also had more decorative textiles than nomads. Urban populations developed more ornamented textiles because the elites in these societies needed indicators of rank and wealth. The general idea was that the more decorative a person’s clothes were, the higher his or her social standing was. Those who were in the upper class of society required clothes which were ever more decorative. Finally, the making of clothes reached a level where an individual artisan could not make prestige textiles without the help of others. At this point specialized groups of textile makers emerged to make it easier to produce these textiles.

However, basic clothing for sedentary Central Asians did not vary a lot. They wore underclothes called tunics, which were also found in 13th century C.E. Mongolian traditional costumes. At first, Central Asian tunics came down to the knees, later they became shorter until the bottom part was at the waist level. Trousers and coats were also basic garments that everyone wore. Therefore, the type of one’s clothes did not tell much about one’s status. However, the material from which those clothes were made did. Thus, basic clothing was essentially the same for all social classes and sexes. But while the lower classes wore coats made of adras (silk and cotton), the elite wore silk and velvet ikats, sometimes embroidered with gold thread.

The Appeal of Oriental Rugs

Central Asians developed a textile culture very early due to the region’s harsh natural environment. Nomads also entered the region, often taking up sedentary lives near oases. These Nomads wore unique clothes such as trousers, and used their textiles for practical tasks. This differed from sedentary societies that used their textiles to express their social standing and build wealth by trading with merchants along the Silk Road. When Islam arrived in Central Asia, it prohibited the use of traditional animal symbols in textiles. Instead, abstract patterns took their place. Mongols, who initially halted the expansion of Islam, engaged artisans and forced them to make luxury textiles for court use. The Timurid dynasty, which followed Mongol rule, also engaged with artisans. These artisans exchanged textile weaving skills and designs with their Chinese counterparts who also worked alongside them. The Emirate of Bukhara, whose textiles were famous for their gold embroidery, succeeded in creating a high demand for them throughout many societies. In the early 1900s, the Russians arrived in Central Asia, bringing with them the railroad and revolutionizing the method of producing textiles. They mechanized the textile industry, setting up workshops for mass rug productions. They also introduced new chemical dyes, especially red. Nowadays, especially after the Soviet break-down in 1990, Central Asian textiles are internationally known and are available to people al over the world via the Internet, which has become a great benefit to the Central Asian economy.

‘Anatolica, Anatolus, Anatoli, Anatolia’ were some of the names used in the Middle Ages by Christians. After Turkmen groups arrived in Anatolia in the 11th century C.E., they adopted these names as 'Anadolu,' which sounded like a "place full of mothers" in their language, while Arabs called the same lands ‘Memaliki Rum’ or "Land of the Romans" because Eastern Romans ruled these lands. Crusaders called the same land ‘Romania,' "Land of Romans."

Turkmen used to live in the harsh desert climate of Central Asia. Winters were stormy, cold and snowy, and summers were very dry and hot. In this harsh environment they used wool to develop the process of felt making and tapestry weaving for their needs since they were herding sheep, goats, camels and other animals in their tribal way of life. They eventually had to move westward to find a more suitable climate and better grass for their animal stocks.

The nomads used their textiles for practical purposes. Textiles and rugs were highly decorative, yet were still a necessity because their nomadic lifestyle required textiles for various practical functions. For instance, the ground inside their dwellings (yurts) had to be covered with rugs in order to make them habitable. Felts and bands which hung around the yurts also served as insulation.

The term ‘oriental rug’ refers to both pile and flat-woven items. They are hand woven from Morocco to China and are used as floor coverings, store bags, pillow covers, saddlebags, prayer mats, tent decorations, and many other uses. As table covers, floor coverings, and simply as precious objects, rugs have been consistently prized in the West since becoming an important part of East-West trade in the 13th to 14th centuries C.E. Today, the traditional appreciation of oriental rugs continues. Rugs add elegance, color, and prestige to a home. Moreover, people today have become aware of the ethnographic importance of these products. We know that rugs woven by village and nomadic women have always been an important part of the marriage dowry. Also, some of the most beautiful and collectible weavings have traditionally been made for utilitarian purposes: as grain and clothing sacks (çuval), as pillow covers (yastık), as prayer rugs (seccadeh), as area rugs (xelle), as saddlebags (heybe), or as ethnic ceremonial and decorative hangings and trappings. Whether one values rugs as elegant floor coverings, as woven art, or simply as precious objects, village and nomadic weavings carry a strength and intensity of the culture that produced them.

Unfortunately, not many tribal groups on the Silk Road survive today. Modern life has rapidly taken over in rural areas and forced nomadic societies into urban lifestyles.

Etymology

The etymology of the term ‘tapestry’ dates back to Greek tapesetos (which certain etymological dictionaries consider to be of Oriental origin; Berthold Laufer, for example, puts forward the case for considering it to be of Iranic origin. The modern neo-Persian term, in the Arabic lexicon, is farş), whence Latin tappetum (and also tapete and tapes), and the derivative forms such as Italian tappeto (there is confirmation of the Bolognese term tapedo in the year 1290, and we also have evidence of the Venetian term tapéo and the Istrian tapio), Anglo-Saxon taeppet (whence modern German Teppich). From the Byzantine tapetion we get the Spanish and Portuguese tapete (of doubtful origin), the French tapiz (present-day tapis) and Provençal tapiz (from which we have the Catalan tapit). Arabic tinfisä is derived from the Byzantine tapetion as well, possibly by way of Aramaic.

The English term 'carpet' comes from Old French carpite, which is in turn derived from the low or post-classical Latin carpita, from the verb carpere meaning ‘to tear’, possibly because of the strip-like shape. The Anglo-Saxson word rug is of Scandinavian derivation, from the Swedish rugg and Icelanding rögg the original meaning having to do with the concept of ruffled or intricate, like a tuft of grass or a lock of hair.

The Arabic term zärbiyä refers to carpets with a striped decorative motif, like a zebra’s hide, and has a modern Italian derivative in zerbino meaning mat.

How Oriental Rugs are Made

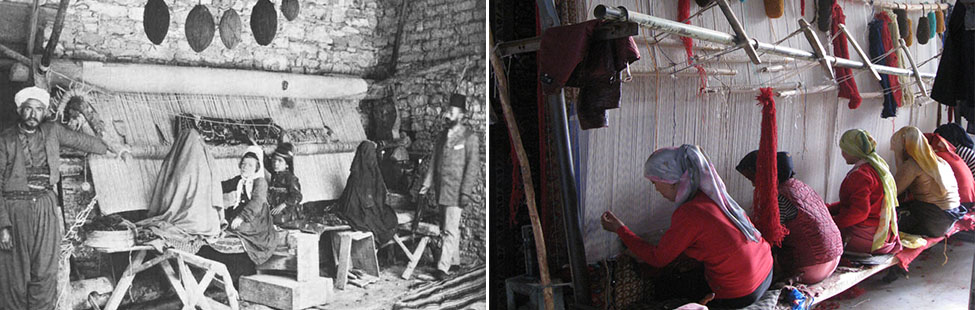

Take a warp or web of threads, or chains arranged lengthwise, and weave or interlace a weft of threads, crosswise. By tying knots between one or more threads of the weft you have a “knotted” carpet. This simple definition is not intended to disguise the complex and numerous factors involved in carpet making. Basically speaking, the technique of knotting a carpet is one of the simplest skills of the artisan. It has undergone very few developments or changes down the centuries, and is still carried on very much as it used to be in olden times. Carpets and textiles are now part and parcel of our common cultural heritage. They have often reached the level of full-fledged works of art, revealing that perfection of proportion and balance, both technical and formal, which is the vital element of any art.

Looms

The carpet is knotted on a loom. Although there are various shapes and sizes of looms, the most common types are still the horizontal and the vertical. As a rule the horizontal, which is easier to operate, was and still is used by nomadic tribes, while the vertical was adopted by sedentary peoples. The technical and mechanical parts of both types are virtually the same, but the results obtained can be quite different. The horizontal loom consists of two usually not very long beams, fixed to the ground with pegs, to which the threads of the warp are attached.